Winter Preparations in the Neighborhood

Quinn Rider, BS Ecology, Behavior, & Evolution

As chilly mornings bring frost and fall colors to Bear Valley, it is time to bid adieu to summer. Winter preparations are officially underway! As folks around the village stockpile firewood and provisions for the coming winter, many of our friends outdoors have their own preparations underway.

Our local critters take one of three approaches to winter here - migration, hibernation, or good old fashioned endurance. With the first snow having already arrived this season, our local mule deer should have already begun their migration down to lower elevations, though they won’t go too far. On average, mule deer migrate to lower elevations between mid October and early November, around when temperatures drop below 40 degrees. Many of our neighborhood inhabitants, like spotted owls and mountain quail, will make similar short scale migrations to below the snow line.

Some of our resident birds will make longer migrations. Neotropical birds like warblers, flycatchers and tanagers, will, as their name suggests, migrate to the neotropics in Mexico, Central America, and South America. Their bodies undergo a number of changes in preparation for their journey. In many of these birds, photoreceptors in their brains register the shortening of the days, triggering a molt that leaves them with new, stronger feathers suited for their long flight. Hormonal changes stimulate appetite, increasing calorie intake so they have extra fat reserves for the journey. Insectivorous birds may change their diets to include fruits and nuts higher in fats to bulk up their reserves.

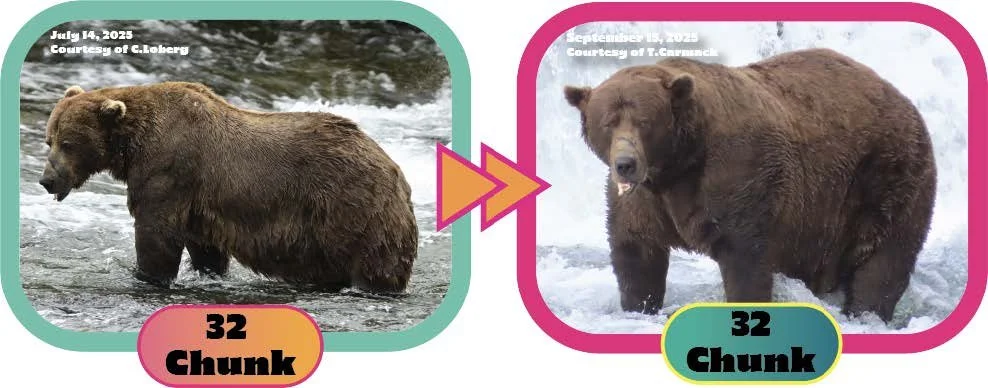

Other neighbors will hunker down to snooze out the winter. Fall is a season of hard work for hibernators, who also need extra caloric stores for their long nap. Bears hibernate, though not all do in the Sierra (for more on that, check out “The Bears are Back in Town” in Quinn’s Eco Corner Series). In late summer and autumn, bears undergo hyperphagia, a temporary physiological state of near-constant foraging and food and water consumption to bulk up winter fat stores. On a regular day, a black bear typically consumes about 5,000 calories. During hyperphagia, they may consume up to four times that, going through about 100 lbs of food a week. Fat Bear Week does an amazing job illustrating the difference hyperphagia can make (if you have never checked out Fat Bear Week, you should). The pictures to the right show the before and after for Grizzly bear 32 Chunk, the winner of 2025’s Fat Bear Week.

Last, but not least, we have a number of particularly hardy little friends who will stay active throughout the winter season! To name just a few, Snowshoe hares, coyotes, and Douglas squirrels will all remain present and active in Bear Valley this winter. They, too are undergoing serious winter preparations to stock up their winter larder… or devise ways to stay out of someone else’s. Spotting a Snowshoe hare in the sparse winter would make many a predator’s day. In an effort to fend off predation, these hares have evolved to molt their brown summer coat to a white one in the autumn, a change triggered by the shortening of the days. Douglas squirrels are busy gathering enough conifer seeds and cones to get them through the winter. Most squirrel species will store many small caches of food, but Douglas squirrels store in bulk. They jealously guard their territory and the hoard within, especially during these months, spearing would-be raiders with their shrill and impressively loud calls that have most certainly been heard by all of Bear Valley’s residents. While coyotes display many traits and adaptations that allow them to survive in the Sierra in the winter (enough to deserve their own article), I did not find anything to suggest that they actively prepare for the season, though they likely bulk up their fat stores if nothing else.

If the recent snowfall has left you scrambling, rest assured, you are not alone. Fortunately for us all, there is still some time left to prepare before winter truly hits. So order your firewood and wax your skis! As surely as the animals feel it in the air, we feel it too. Winter is just around the corner.

Citations

Barta Zoltán, McNamara John M, Houston Alasdair I, Weber Thomas P, Hedenström Anders and Feró Orsolya 2008. Optimal moult strategies in migratory birds Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B363211–229 http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2136

Daw, Sonya. “Douglas’s Squirrel (U.S. National Park Service).” Www.nps.gov, Jan. 2021, www.nps.gov/articles/000/douglas-s-squirrel.htm.

“Fat Bear Week 2025.” Explore.org, 2025, explore.org/fat-bear-week.

“How Do Birds Prepare for Long Migrations?” All about Birds, 1 Apr. 2009, www.allaboutbirds.org/news/how-do-birds-prepare-for-long-migrations/.

Meyer, Rachelle. “Strix Occidentalis.” Www.fs.usda.gov, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, 2007, www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/animals/bird/stoc/all.html.

Monteith, K. L., V. C. Bleich, T. R. Stephenson, B. M. Pierce, M. M. Conner, R. W. Klaver, and R. T. Bowyer. 2011. Timing of seasonal migration in mule deer: effects of climate, plant phenology, and life-history characteristics. Ecosphere 2(4):art47. doi:10.1890/ES10-00096.1

“Mountain Quail.” Audubon, 13 Nov. 2014, www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/mountain-quail.

National Park Service. “Snowshoe Hare (U.S. National Park Service).” Nps.gov, 2017, www.nps.gov/articles/snowshoe-hare.htm.

Nelson, Ralph A., et al. “Behavior, Biochemistry, and Hibernation in Black, Grizzly, and Polar Bears.” Bears: Their Biology and Management, vol. 5, 1983, pp. 284–90. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3872551.

Wilson EC, Shipley AA, Zuckerberg B, Zachariah Peery M, Pauli JN. An experimental translocation identifies habitat features that buffer camouflage mismatch in snowshoe hares. Conservation Letters. 2019; 12:e12614. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12614